Kumbh Mela in Nashik

Article and Photography by John Werner

“The world’s largest city has no permanent address.”

The largest city in the world has 100 million people, but no permanent location. Built by pilgrims in India for a religious gathering called the Kumbh Mela, it exists for just a month and a half out of every 12 years. Three sister pilgrimages draw tens of millions of pilgrims. What can we learn from these self-organizing gatherings to hack the world’s permanent mega cities?

Millions of people waiting to take five dips in the holy river.

The story goes, in the Hindu tradition, that during a mythical war between the Devas and the Asuras over the Amrita, or Nectar of Immortality, four drops of nectar spilled over four spots on Earth. As a result, four cities at those locations today – Haridwar, Prayag (Allahabad), Ujjain, and Nashik in India-all hold Kumbh Melas, massive religious gatherings of tens of millions of pilgrims. The Kumbh Mela in Nashik takes place every 12 years when Jupiter, the Sun and the Moon enter Leo constellation – which is now.

Preparing for Kumbh Mela with Innovations

I have been to India nine times before to help launch our health innovation efforts in Hyderabad and Mumbai. On many of those trips I have swung by Nashik to prepare for the Kumbh Mela. But this time, I travelled to Nashik and found myself by the river Godavari during the Kumbh Mela itself, and saw that many of the projects that began as the dreams of innovators were now being deployed. These innovators themselves are an amazing mix of high school students, college-goers, part-time workers, job-quitters and entrepreneurs, who came together under this platform to build impactful and unique solutions.

I was witness to a large crowd of more than 2.5 million that had gathered on August 29, 2015 for the Shahi Snan, a hugely important cultural and religious ceremony. I left at 3 am to travel to the heart of this event. Pilgrims from all parts of India were at the Shahi Snan area by 7 am to have the privilege of bathing in the holy river.

I woke up at 3 in the morning and headed to the ceremony.

Pilgrimage sites in other parts of the world such as Mecca and Karbala, have permanent infrastructure to handle necessities such as food, lodging, ritual bathing, group prayer and other related activities. Such events are carefully planned and coordinated in advance to keep everything running smoothly.

But Kumbh Mela, one of the largest religious congregations in the world, is an organizational challenge to pull off. The officials of Nashik send in large numbers of police and set up makeshift wooden fences for security reasons, and many more preparations need to be done in order to receive the tens of millions of pilgrims for this 40 day event. Food, water, lodging, restrooms, medical and emergency services, and dozens of other things all have to be arranged for. Not an easy task.

The police help keep the Kumbh Mela running. The mayor was interviewed by the local press.

Nashik municipality created detailed maps and labeled key places of Kumbh Mela.

Signs and wood fences were created to help maintain organization as millions move around Nashik.

River of Data

As a facilitator of local innovation, I am constantly thinking about the River of Data: how can information and data technology benefit a large community like the Kumbh Mela pilgrims? The opportunities for improvement are obvious: we can help avoid deadly stampedes, disease outbreaks, and children becoming separated from their parents in a crowd of millions. Over 18 months, I witnessed our innovators thinking about how technology could be used to make Kumbh Mela a safer, richer, more accommodating, and more satisfying experience.

In Nashik and at the MIT Media Lab, innovators have been working to identify modular, portable, and scalable solutions for this, one of the world’s largest congregations. We hope to instill among Indian citizens a spirit of innovation by coming up with workable, low-cost, grassroots solutions to problems that Nashik locals identify as important. This idea grew from multilingual platform developer and entrepreneur Sunil Khandbahale and Nashik-raised MIT Professor Ramesh Raskar to now include an impressive array of partners, including Indian government agencies, academia, non-profits and large global corporations. Central to it are innovators and entrepreneurs who have been participating, armed with passion and ideas. They are rolling out their solutions to other markets across the globe. They are what Raskar calls “a new generation of social entrepreneurs.”

Low-cost, high-impact, technology-based solutions are encouraged, focusing on data and mobility. Other requirements include the need for little or no capital, and the ability to easily scale using existing infrastructure. For example, more than 930 million of India’s 1.2 billion people are cell phone subscribers, meaning that mobile apps have enormous potential for impact while requiring very little in the way of resources, materials, or new infrastructure. TCS, for example, introduced its WhatsApp-like in-house social platform, Gappa Goshi (chitchat), to study crowd mood and help authorities with various policy frameworks based on the collected data.

The woman in the middle of the photo is holding her phone. In India, there are 900 million cell phone users–almost three times the entire population of U.S.

Press covering the event with a mobile phone. With so many cell phone users, the potential for mobile technology is enormous in India.

REDX Clubs, an Innovation Platform

We are now looking into creating a way to scale this process and create a platform that other young local innovators can connect to. Every time I visit India, I’m awestruck by the amazing innovation and invention young people are capable of. And when I’m flying back, looking out over the countries below, I imagine what kinds of things could be accomplished if we could spread that kind of innovative spirit across the entire world. And so, the REDX Clubs, as we’re calling them, stand for Rethinking Engineering Design Execution, and they will draw on the best of this innovation, scaling this process of spotting and probing and bringing it to the next generation of innovators around the world.

Innovation in Nashik

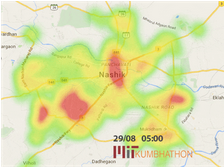

On this trip I was impressed with the work that innovators had done. Over the years, the MIT Media Lab has formed a close collaboration with innovators from Nashik, successfully holding several Kumbhathons, founding several REDX Clubs, and encouraging local innovation and exchange between MIT and India. Under the mentorship and facilitation of the MIT Media Lab, student innovators have made incredible achievements, working to make Nashik a smart city. Recently, the MIT Media Lab collaborated with local organizations in Nashik on many projects that involved data and information technology. The city of the future will built around the massive amounts of data ebbing and flowing through our lives. One of their projects was Crowd Steering, which identifies the count and monitor the flow of people geographically to enable provides better transport and resource planning by administration and consumers.

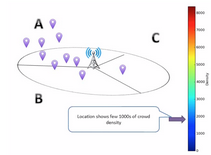

We estimate the population by counting the mobile devices, which are always registered and attached to a nearby tower, and the telecom operators report the number of devices gathered within a certain distance of a tower. Then we can map out the population density around certain areas in the city. This technology has huge potential, especially in countries with large populations like India. The count provides administration with up-to-date information about traffic, so that the city can make better traffic arrangements. The dedicated team pulled off multiple all-nighters to get the solution up and running in time for the Royal Bath, which witnesses a tremendous influx of pilgrims into Nashik.

Cell towers in Nashik, where the data flows.

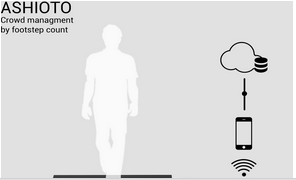

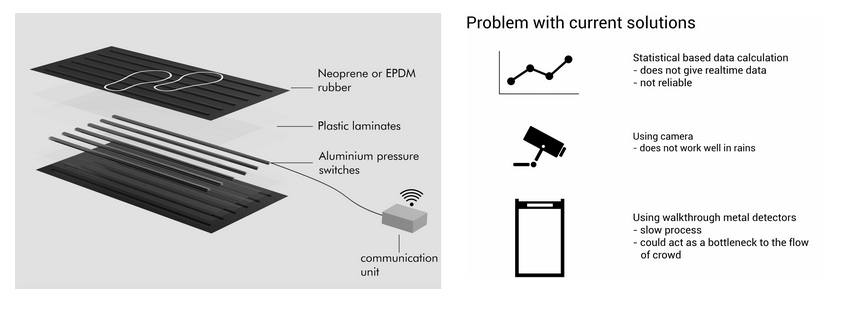

A similar project is Crowd Management by using footstep count. After analyzing the disadvantages of other monitoring devices, a 15-year-old invented the footstep-counting device, a carpet looking device that can track population traffic by counting how many people have stepped on it.

This simple yet effective device can be placed on any streets, providing realtime population measurement data to our monitoring team. Compared to other solutions, this device is low cost, easily scalable, and consistent in poor weather conditions. The significance of this device is to avoid stampede and false alarm, and to supply resources according to population density and crowd flow data. The device can be easily placed on any street, overseeing traffic and reporting to databases.

The 15 year old innovator who drove this project.

Our team also created an Official application for the Kumbh, named the official portal for all Kumbh Mela-related information from maps to food to emergency assistance.This app includes many necessary tools for residents in this area such as Crowd Flow, Kumbh Mela Details, Transportation, and local news. This comprehensive app links people with an online database, giving them updates about the city so that they can make smart decisions and avoid inconveniences. I believe the official Kumbh app successfully uses data analyzation and information technology to benefit the local residents and tourists of the Shahi Snan, and therefore improves their living standard in this city. After it went online, the app had had thousands of downloads and received high ratings from its users.

The official Kumbh app interface

In my previous trips to India, I had noticed the poor housing structures in slums. City officials have little regulation or control over them. This time, we worked with Sampath Reddy, a local engineer, to build Pop-up Housing, a frame-based housing that can be constructed in only 3 days and that now has an installation in the government-sponsored temporary housing area. This housing installs pallet rack-based housing kits and eco friendly building solutions using indigenous methods and reusable industrial materials. This mass-produced, low cost, low skill, and high- density construction provides city officials with an alternative housing option for poor areas in the country, solving the problem of increasing urbanization in India. Pop-up Housing has huge potential in the market because it can be used for many different purposes, including student housing, migrant hostels, transit camps, and disaster relief.

Construction site of Pop-up Housing.

The first pop-up structure was originally built to serve as the local Nashik Municipal Corporation headquarters for the area, but a group of nearby Sadhus who owned the surrounding property liked it so much that they decided to move in themselves! At present, the two groups are negotiating over who gets to keep the building. Sampath Reddy, the lead engineer on the project, says he doesn’t personally have any issues over who uses the building, so long as it gets used extensively!

Sampath Reddy, leading engineer of the pop-up housing project

Another exciting project to come of of Kumbhathon was Wiki Nashik. When the team looked at Nashik’s presence on Wikipedia, they found that the page had next to no information on the city of over one million inhabitants. In this day and age, where Internet presence is everything, being invisible on the web can make you seem irrelevant. So, they decided to change that: starting with a team of 50 volunteer innovators under the direction of Santoshi Tiwari, they began gathering information about Kumbh Mela, history, mythology, points of interest, and other topics to put on the page. Through the Wikipedia Awareness Drive at Bytco College in Nashik and other crowdsourcing efforts, the page quickly grew to have over 2,000 pageviews per day.

The Wiki Nashik project had a big enough impact that their article got articles written about it!

Emerging Worlds, a Broader Effort

Nowadays the world is changing drastically and rapidly, fueled by innovations and new ideas. People therefore have to constantly reinvent themselves to stay ahead. Deploying and scaling new technologies will eventually benefit the citizens, not just of Nashik, but of other cities where such efforts can be deployed. This effort is part of a series of similar initiatives to engender the next-generation of smart cities by smart-citizens, called Emerging Worlds. In Emerging Worlds, our interface with digital and physical systems is being transformed through evolving technologies. We are building an open innovation platform that can engage researchers and scientists in deep conversations about improving emerging communities worldwide, and connect exciting projects with stakeholders and local change-makers via innovation sandboxes called “launch-boxes”. As we continue to foster innovation, there will be more developments and applications for data and information technology in the near future.

Closing

In closing, I am excited and honored to witness the changes that have and will happen in Nashik and to use Kumbhathon as a platform to bring together stakeholders, innovators and private corporations to build technologies that understand and respond to human activities. Analyzing data and information gives us an approach to build the smarter and better functioning city of the future.

Here are a few more pictures that I took during my trip in Nashik that could give you some ideas about its culture and future possibilities:

Pilgrims rushing to the holy river.

Sadhus preparing for the ceremony.

A Sadhu at Kumbh Mela.

Our team monitoring incoming data in a mall.

A Google and a Yahoo Engineer who dropped by and took time to mentor our innovators!

Professor Raskar analyzing data with local Innovators.

A “pop-up” bus stop to help the Kumbh Mela pilgrims get around Nashik.

Nashik is the wine capital of India – here are some of the grapes it is known for.

Camel at the Kumbh Mela.

Landscape of Mumbai at night as I flew out of India my 9th time – inspired by the innovators I’ve had the opportunity to work with.